- The American Trends Panel survey methodology

Mental health concerns top the list of worries for parents; most say being a parent is harder than they expected

Pew Research Center conducted this study to better understand how American parents approach parenting. This analysis is based on 3,757 U.S. parents with children under age 18. The data was collected as part of a larger survey of parents with children younger than 18 conducted Sept. 20 to Oct. 2, 2022. Most of the parents who took part are members of the Center’s American Trends Panel (ATP), an online survey panel that is recruited through national, random sampling of residential addresses. This survey also included an oversample of Black, Hispanic and Asian parents from Ipsos’ KnowledgePanel, another probability-based online survey web panel recruited primarily through national, random sampling of residential addresses.

Address-based sampling ensures that nearly all U.S. adults have a chance of selection. The survey is weighted to be representative of the U.S. adult population by gender, race, ethnicity, partisan affiliation, education and other categories. Read more about the ATP’s methodology.

TerminologyThroughout this report, references to parents, including mothers and fathers, include only those who currently have a child younger than age 18.

References to White, Black and Asian adults include only those who are not Hispanic and identify as only one race. Hispanics are of any race.

All references to party affiliation include those who lean toward that party. Republicans include those who identify as Republicans and those who say they lean toward the Republican Party. Democrats include those who identify as Democrats and those who say they lean toward the Democratic Party.

“Middle income” is defined here as two-thirds to double the median annual family income for panelists on the American Trends Panel. “Lower income” falls below that range; “upper income” falls above it. See the methodology for more details.

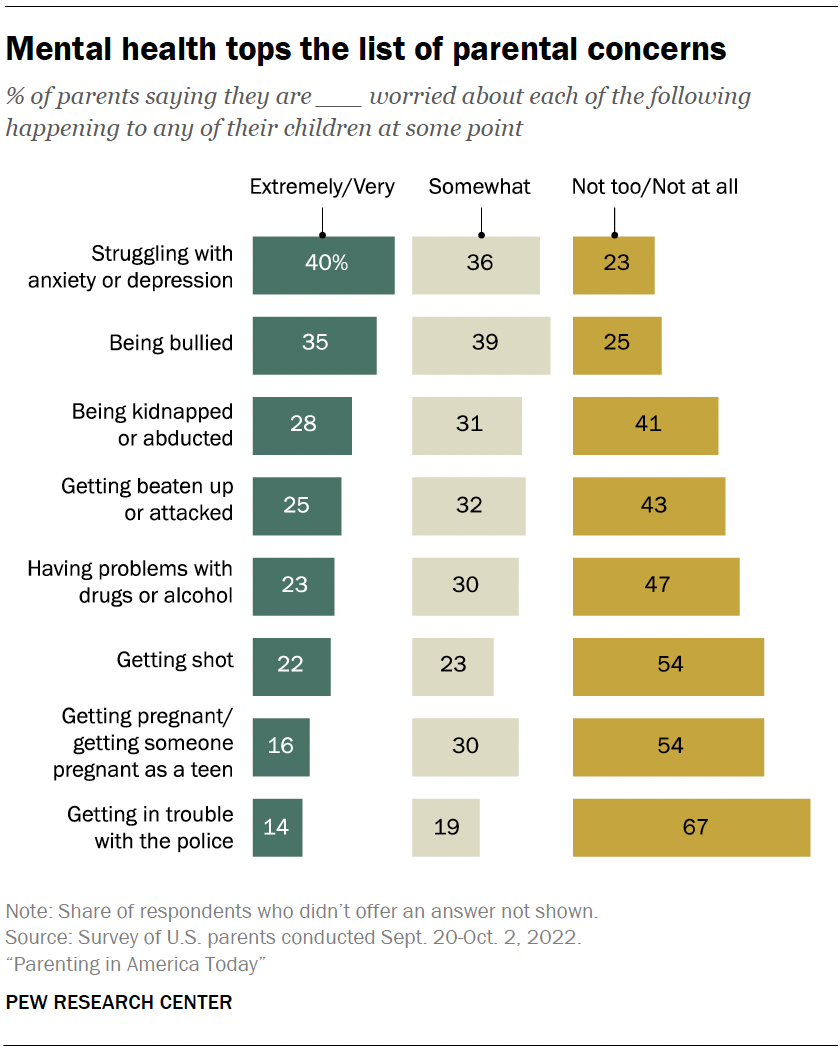

In the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic and amid reports of a growing youth mental health crisis, four-in-ten U.S. parents with children younger than 18 say they are extremely or very worried that their children might struggle with anxiety or depression at some point. In fact, mental health concerns top the list of parental worries, followed by 35% who are similarly concerned about their children being bullied, according to a new Pew Research Center survey. These items trump parents’ concerns about certain physical threats to their children, the dangers of drugs and alcohol, teen pregnancy and getting in trouble with the police.

By significant margins, mothers are more likely than fathers to worry about most of these things. There are also differences by income and by race and ethnicity, with lower-income and Hispanic parents generally more likely than other parents to worry about their children’s physical safety, teen pregnancy and problems with drugs and alcohol. Black and Hispanic parents are more likely than White and Asian parents to say they are extremely or very worried about their children getting shot or getting in trouble with the police.

(Differences in parental worries, approaches to parenting, and parents’ goals and aspirations are explored in more depth later in this report. The chapters focus on distinctions by gender, race and ethnicity, and income level.)

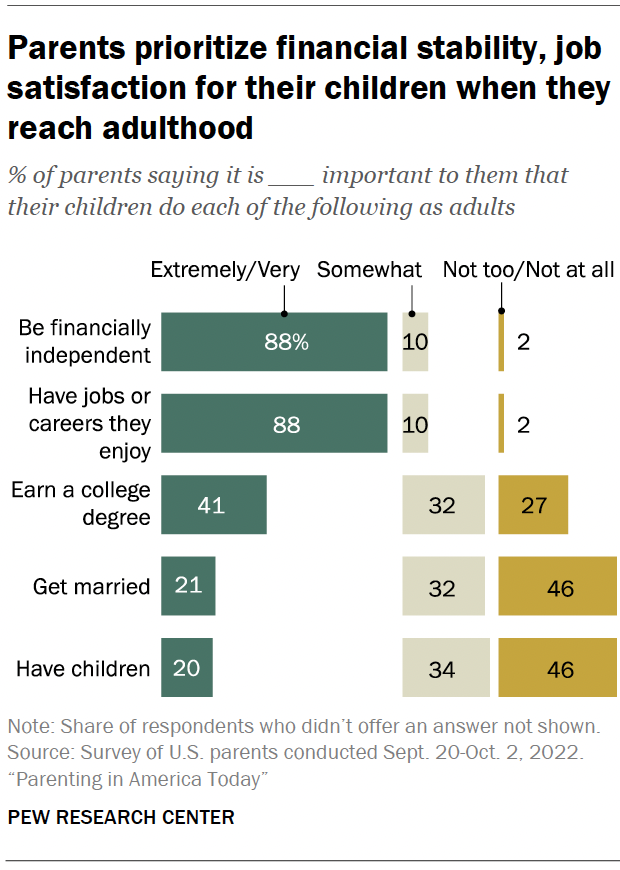

When asked about their aspirations for their children when they reach adulthood, parents prioritize financial independence and career satisfaction. Roughly nine-in-ten parents say it’s extremely or very important to them that their children be financially independent when they are adults, and the same share say it’s equally important that their children have jobs or careers they enjoy. About four-in-ten (41%) say it’s extremely or very important to them that their children earn a college degree, while smaller shares place a lot of importance on their children eventually becoming parents (20%) and getting married (21%).

There are sharp differences by race and ethnicity when it comes to the importance parents place on their children graduating from college: 70% of Asian parents say this is extremely or very important to them, compared with 57% of Hispanic parents, 51% of Black parents, and just 29% of White parents.

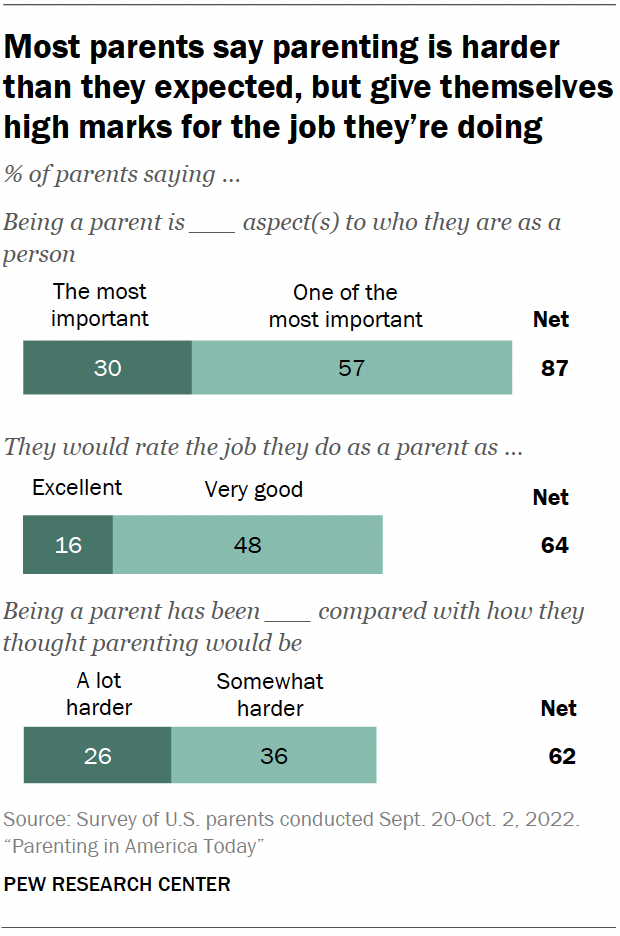

In a nod to the adage about family life that parenting is the hardest job in the world, most parents (62%) say being a parent has been at least somewhat harder than they expected, with about a quarter (26%) saying it’s been a lot harder. This is especially true of mothers, 30% of whom say being a parent has been a lot harder than they expected (compared with 20% of fathers).

At the same time, most parents give themselves high marks for the job they’re doing, with 64% saying they do an excellent or very good job as a parent; 32% say they do a good job, while just 4% say they do an only fair or poor job as a parent. Mothers and fathers give themselves similarly high ratings, but there are differences by income and by race and ethnicity (upper-income and Black and White parents are the most likely to say they do an excellent or very good job).

While a relatively small share of parents place a high level of importance on their own children having children one day, the vast majority – including among mothers and fathers and across income and racial and ethnic groups – describe being a parent as the most (30%) or one of the most (57%) important aspects to who they are as a person. Mothers (35%) are more likely than fathers (24%) to say being a parent is the most important aspect. And Black (42%) and Hispanic (38%) parents are more likely than White (25%) or Asian (24%) parents to say the same.

These are among the major findings of the nationally representative survey of 3,757 U.S. parents with children younger than 18, conducted Sept. 20-Oct. 2, 2022, using the Center’s American Trends Panel. 1 Other findings from the survey:

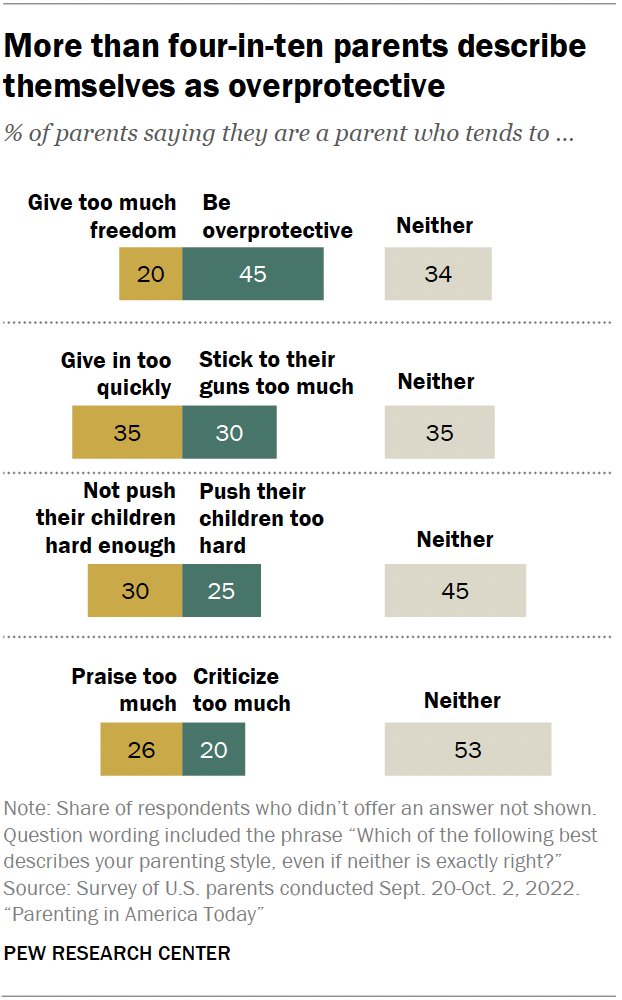

Parents often don’t adhere to a specific parenting style. When asked whether they’re a parent who tends to stick to their guns too much or give in too quickly, praise or criticize their children too much, be overprotective or give too much freedom, and push their children too hard or not hard enough, shares ranging from 34% to 53% say neither option best describes their parenting style. Still, more than four-in-ten parents (45%) say they tend to be overprotective, compared with 20% who say they tend to give too much freedom. And somewhat larger shares say they tend to give in too quickly (35%) rather than stick to their guns too much (30%), praise their children too much (26%) rather than criticize them too much (20%), and not push their children hard enough (30%) rather than push them too hard (25%).

There are wide differences in some of the ways mothers and fathers describe their parenting style. For example, about half of mothers (51%) say they tend to be overprotective, compared with 38% of fathers. In turn, fathers (24%) are more likely than mothers (16%) to say they tend to give their children too much freedom. Mothers are also more likely than fathers to say they tend to give in too quickly (40% vs. 27%, respectively), while fathers are more likely to say they stick to their guns too much (36% vs. 24% of mothers).

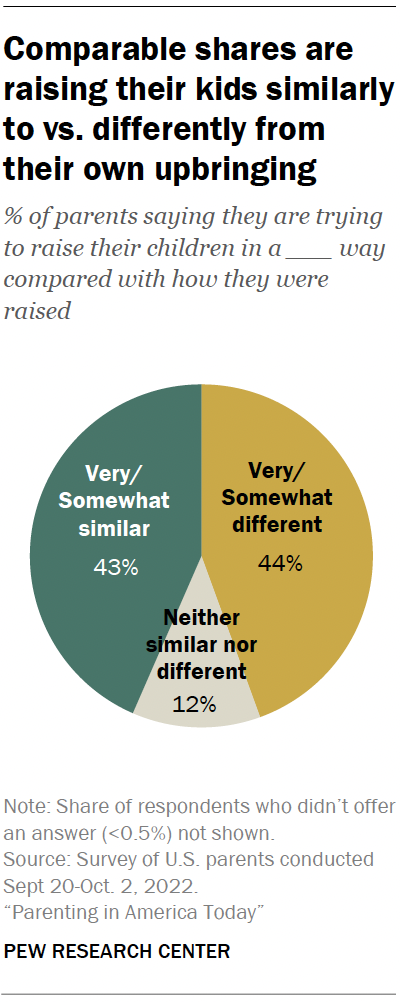

Roughly as many parents say they are trying to raise their children in a similar way to how they were raised (43%) as say they are trying to raise them differently (44%). Fathers are more likely to say they are raising their children in a similar way to how they were raised (47%) than to say they are raising them differently (40%). In turn, 48% of mothers say they are trying to raise their children differently from how they were raised, while 40% say they are trying to raise them in a similar way.

There are also differences along racial, ethnic, and income lines. About half (49%) of White parents say they are raising their children in a similar way to how they were raised, compared with 42% of Black parents, 37% of Asian parents and 32% of Hispanic parents. And while 51% of parents with upper incomes say they are trying to raise their children similarly to how they were raised, smaller shares of those with middle (46%) and lower (35%) incomes say the same. (For more on the ways in which parents are trying to raise their children in a similar or different way to how they were raised, see How Today’s Parents Say Their Approach to Parenting Does – or Doesn’t – Match Their Own Upbringing.)

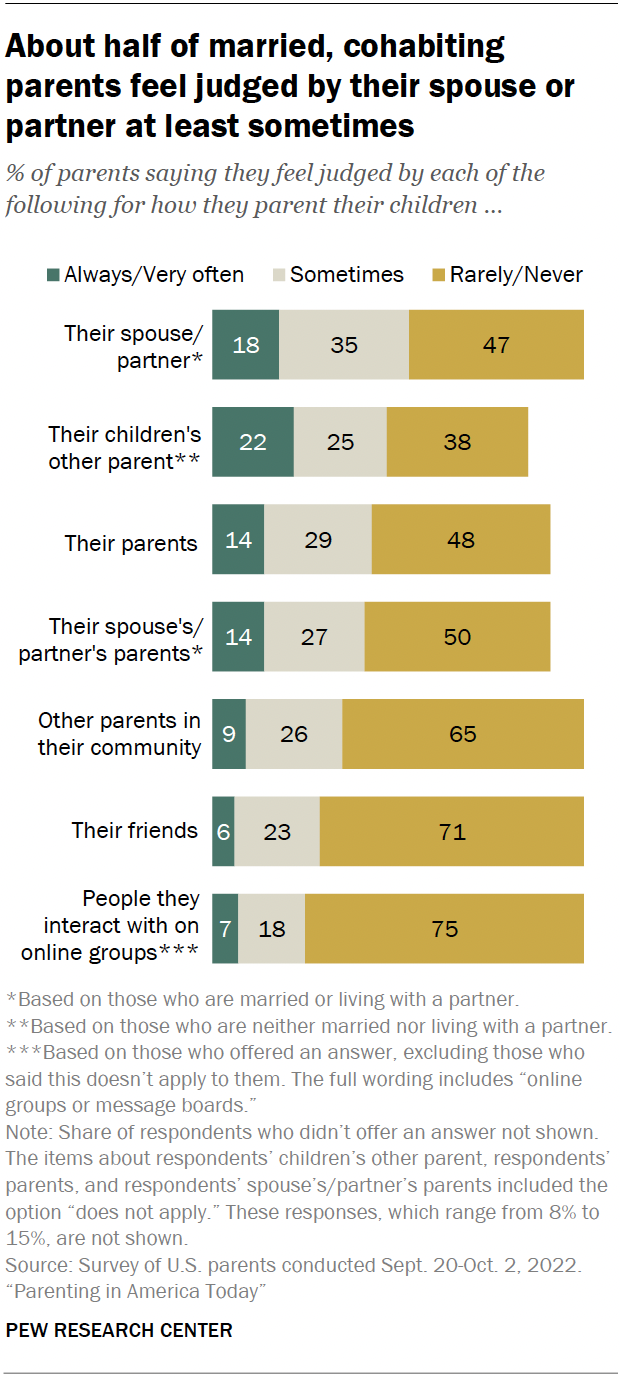

Parents are more likely to say they feel judged by family members than by their friends, other parents in their community or people they interact with online. About half of married or cohabiting parents (52%) say they feel judged by their spouse or partner for how they parent their children at least some of the time, with 18% saying they feel this way always or very often. About four-in-ten or more parents also say they feel judged by their own parents (44%) and their spouse or partner’s parents (41% among those who are married or cohabiting) at least sometimes. Smaller shares say they feel judged at least sometimes by other parents in their community (35%), their friends (29%) or people they interact with on online groups or message boards (25% who offered an answer, excluding those who said this didn’t apply).

Among married and cohabiting parents, fathers are more likely than mothers to say they feel judged by their spouse or partner at least sometimes for how they parent their children, but mothers are more likely than fathers to say they feel judged by people other than their spouse or partner. There are also some differences by race and ethnicity, with Asian parents more likely than other racial or ethnic groups to say they feel judged by their own parents and White parents more likely than other groups to say they feel judged by other parents in their community.

While about half or fewer parents say they regularly feel judged by different groups, a majority of parents (57%) say they think their children’s successes and failures reflect a great deal or a fair amount on the job they’re doing as a parent. About a third (34%) say they reflect some, and just 9% say they do not reflect much or at all on their job as a parent.

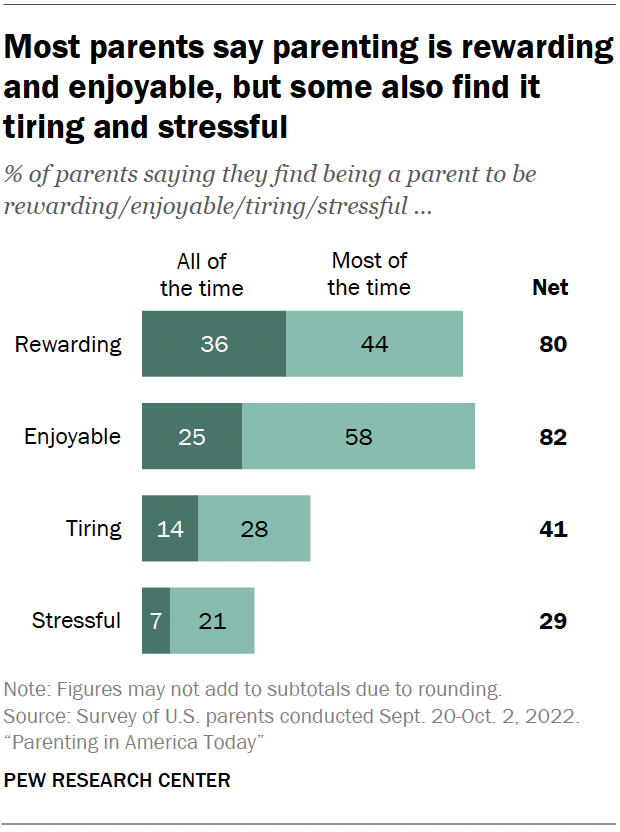

The vast majority of parents say being a parent is enjoyable and rewarding all or most of the time, but substantial shares also find it tiring and stressful. About four-in-ten parents (41%) say being a parent is tiring and 29% say it is stressful all or most of the time. Mothers and fathers are about equally likely to say being a parent is enjoyable and rewarding, but larger shares of mothers than fathers say parenting is tiring (47% vs. 34%) and stressful (33% vs. 24%) at least most of the time.

Experiences also vary based on the ages of the children. Parents with children younger than age 5 are more likely than those whose youngest child is 5 or older to say they find parenting to be tiring and stressful. A majority of those with children in the youngest age group (57%) say being a parent is tiring all or most of the time, compared with 39% of those whose youngest child is 5 to 12 years old and 24% of those whose youngest child is a teenager. And while about a third (35%) of those with a child younger than 5 say parenting is stressful all or most of the time, about a quarter of those whose children are all 5 or older say the same.

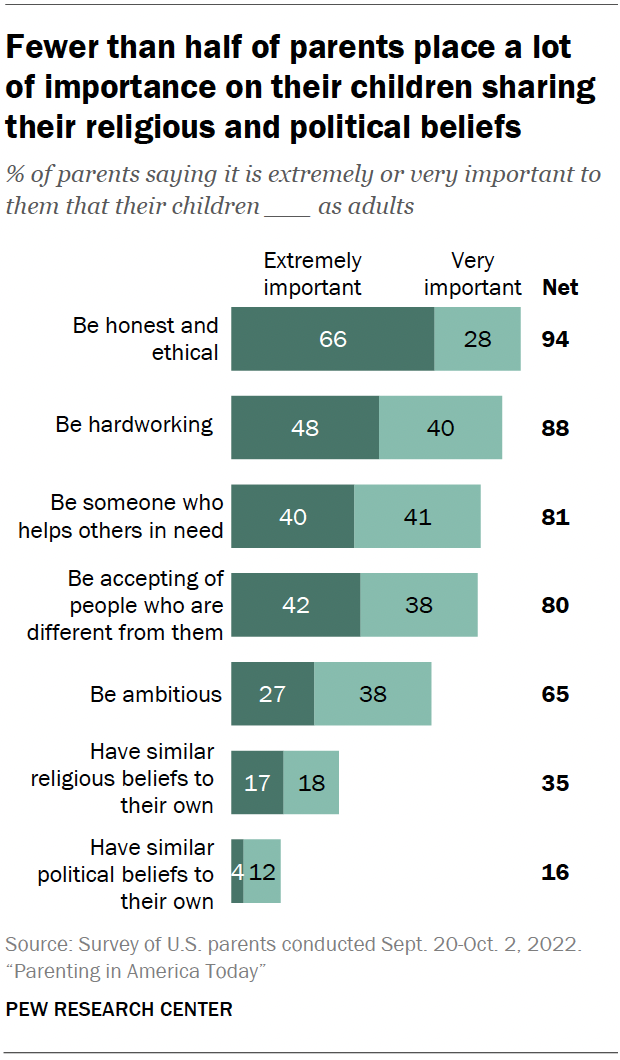

In thinking about the kind of people they hope their children will be as adults, parents place the most emphasis on their children being honest and ethical. About two-thirds of parents (66%) say it’s extremely important to them that their children grow up to be honest and ethical adults. About half (48%) say the same about their children being hardworking, while about four-in-ten say it’s extremely important to them that their children become the kind of people who are accepting of people who are different from them (42%) and who help others in need (40%). A smaller share (27%) place this level of importance on their children being ambitious as adults. Majorities ranging from 65% to 94% say it is at least very important that their children have each of these traits as adults.

Parents place less importance on their children growing up to have religious or political beliefs that are similar to their own. About a third (35%) say it is extremely or very important to them that their children share their religious beliefs, and 16% say the same about their children’s political beliefs. Republican and Democratic parents are about equally likely to say it’s at least very important to them that their children share their political beliefs.

About four-in-ten Black (40%) and Hispanic (39%) parents say it’s extremely or very important to them that their children share their religious beliefs; 32% each among White and Asian parents say the same. White evangelical Protestant parents (70%) are more likely than White non-evangelical Protestant (29%) and Black Protestant parents (53%) to say it’s very or extremely important to them that their children have religious beliefs that are similar to their own as adults. About a third (35%) of Catholic parents and just 8% of those who are religiously unaffiliated say this.